Thirty minutes into Mothmen 1966, it doesn’t take long for me to develop a favourite character – Holt, a crusty white-haired gas station attendant who probably spends too much time on his own. Ten minutes later, and I’m hopelessly fixated, thanks to my worst compulsive tendencies, on Holt’s grandmother’s favourite game: Impossible Solitaire. Even when I’m not a hundred percent on board where the story is going, Mothmen 1966 is a magnetic little bubble enveloped in darkness, and it’s hard to slow down – I almost feel guilty for clicking through each page a little too fast, thanks to the almost bewitching, alienating mood created by limited old ZX Spectrum colours from a bygone era.

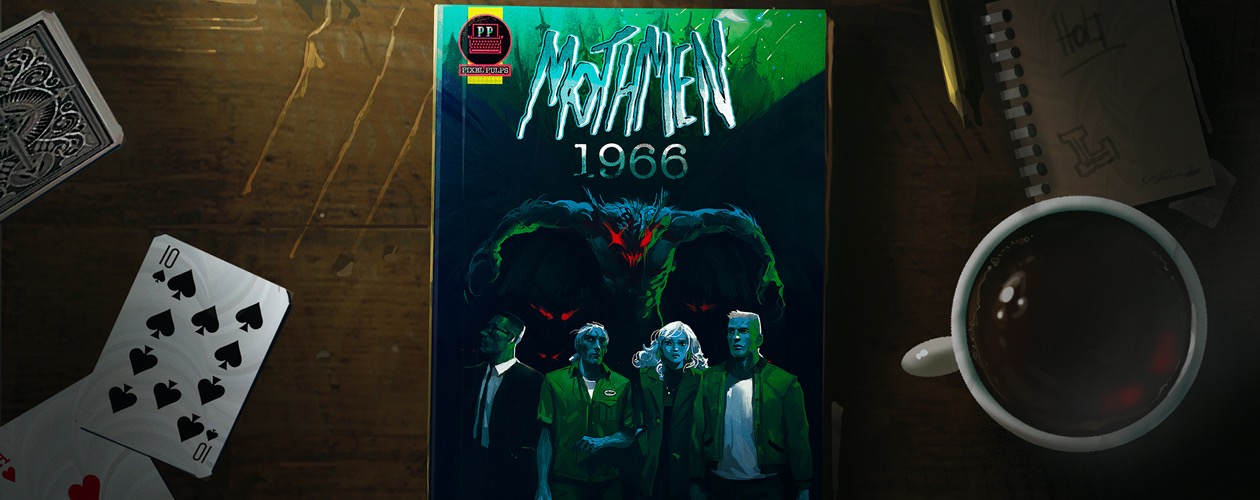

This isn’t the first “pixel pulp” from LCB Studios, but it’s definitely the longest and most fleshed-out game in their catalogue so far. These are short, pulpy visual novels that draw inspiration from old sci-fi/fantasy and horror paperbacks filled with serialised short stories and otherworldly art from decades past. Mothmen 1966 isn’t so much of a traditional narrative as a prolonged glimpse into a very weird night in the woods, told through three playable characters: Holt, Victoria, and Lee. As with most pulp storytelling where writers didn’t have a lot of time to set the stage and mood, the game relies on potent imagery and tropes from “golden age” sci-fi and horror as thematic shorthands: a young couple heading to a secluded area in the name of romance, a curmudgeonly loner with odd hobbies, an ominous encounter with wild animals.

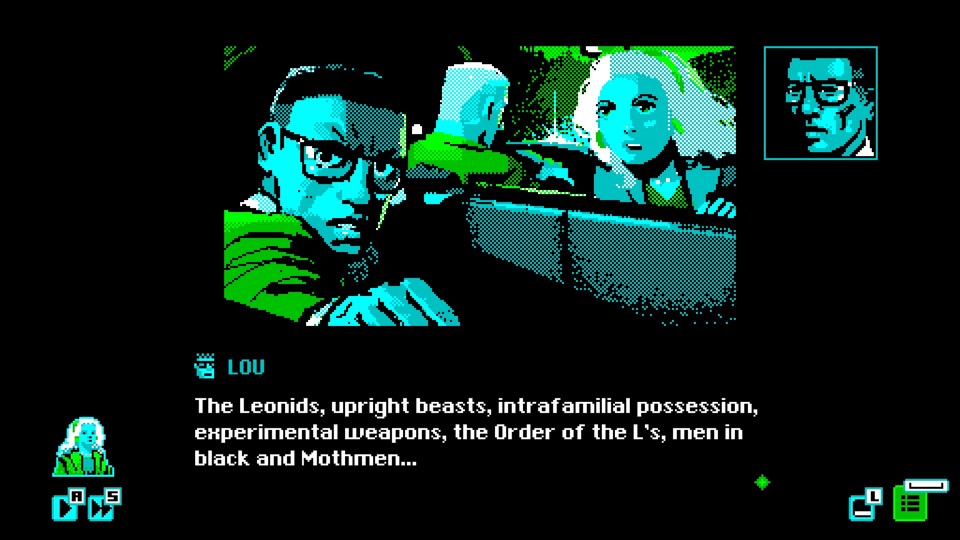

The game is structured as short, alternating chapters between the three characters. Victoria and Lee seem like a picture-perfect college couple – Lee has a surprise planned for his girlfriend, which involves driving out to Holt’s neck of the woods. Holt has his own strange encounter with sinister G-men, and dwells on his personal side project working on his grandfather’s legacy – fixing a Winans steam gun, a strange relic from the Civil War that fell into obscurity. When Lou Hill shows up – an eccentric writer who specializes in Fortean arcana and the occult – the eponymous mothmen aren’t far behind. At the heart of it all – the legendary Leonid meteor shower of 1966, one of the most remarkable recorded instances of the annual Leonid storms that occur over central and western North America.

The thing about LCB’s pixel pulps (this is only their second fully launched game; their third, Bahnsen Knights, has been in the making for a bit) is how much character and nuance they can pump out within the technical restraints of their chosen aesthetic. Besides the occasional use of subtle animation, there’s a smart, repeated use of triptychs to simulate movement and progress, which ties into graphic novels and LCB’s inter-genre artistic approach. Dramatic lighting, shadows, and artful dithering create an ominous atmosphere that builds with each scene.

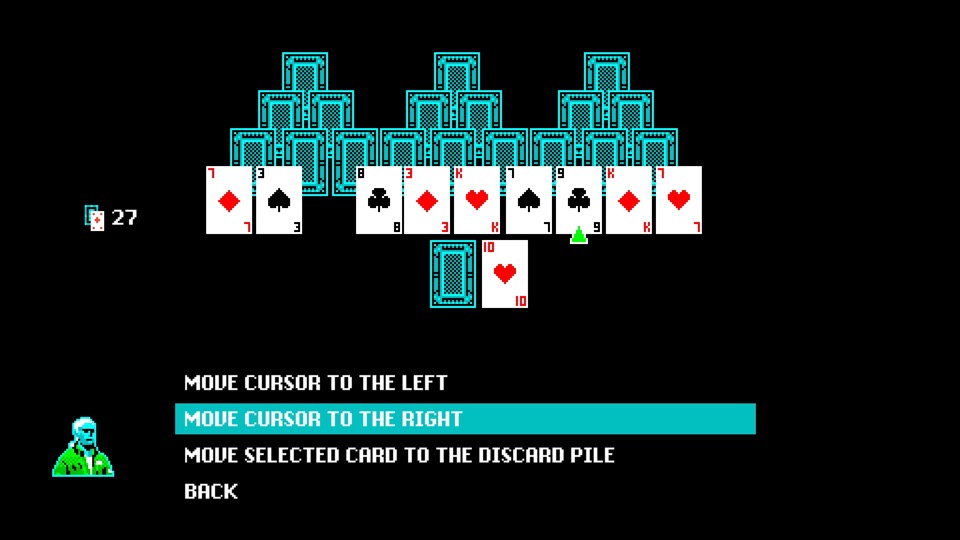

The mini-games, peppered throughout the main narrative, are mostly a nice diversion from the plain text options, with the exception of Holt’s straightforward, tedious shelf-sorting sequence that feels, at best, like an interactive tutorial/prelude to later puzzles. The Impossible Solitaire game was a particularly nice touch – it’s both an in-game sequence as well as a standalone mini-game that can be accessed from the main menu. It’s based on a solitaire variation called Tripeaks with a little added twist – tough on the outset but solvable if you pay attention to the deck (or are naturally savvy at card or suit counting), especially one telltale bitten card thanks to a previous scene in the game.

Another favourite was a neat turn-based mini-game full of monster enemies that required a little more strategy, using the Winans steam gun to fire in one of three directions (possibly a little homage to old-school ZX Spectrum games). My biggest frustration here was the kneejerk instinct, as a ‘modern’ player, to drag-and-drop or interact directly with the graphics – all mini-game commands are performed through text options, which can get tedious, especially with the puzzle mini-game.

Working with such a fast, furious format and genre yields conflicting feelings as a player. LCB’s first pixel-pulp Shark Riders is a heady hallucinogenic action movie that would absolutely rock as a short film or animation – the story unfolds like a heavy metal concept album with a raw, primeval sense of urgency and recklessness. Mothmen 1966 is a different beast altogether – there’s the same general sense of heady adventure and momentum that, at times, feels stymied by the short chapter breaks and occasional detours into historical exposition.

It’s not the same action-packed exhilaration as Shark Riders, a leaner, wilder narrative which beautifully complemented the compact scope of the game. The pixel-pulp art and writing style leans towards impulse and adrenaline, and it’s a little hard to let go of this instinctive drive when faced with a more unwieldy, multi-character narrative. Lee in particular doesn’t stand on his own legs as well as the others, and Lou’s obtuse quirks and affectations don’t always hit the right note for effective parody or caricature.

All that being said, Mothmen 1966 remains a sublime experiment, an intriguing narrative diversion, and a loving tribute to cryptozoology and old computer graphics. If pixel-pulps are meant to be produced quickly and intensely like the pulp fiction they take their name from, they also stand for the continuation of a long, storied history of lurid, exciting storytelling that flourishes within specifically chosen technical restraints.